Imagine seeing the world through a veil of static, like looking at a badly tuned old television set. This isn’t just a fleeting illusion; it’s the continuous reality for people living with visual snow syndrome, a rare neurological disorder that affects vision and can bring with it a host of other challenging symptoms.

Scientists first recognized this condition in 1995, though it wasn’t officially named until a 2015 study. Despite having been observed for decades, visual snow syndrome remains little-known, both among the general public and, to a degree, even among experts, who readily admit they have much more to learn about its origins and mechanisms.

The core characteristic of visual snow syndrome is the persistent perception of tiny, snowlike flecks across the entire visual field. These dots are typically black and white, though they can sometimes appear transparent. The static vision remains constant, even when the eyes are closed.

This perpetual visual disturbance can be debilitating for some individuals, impacting their ability to work effectively or complete schoolwork. It’s a constant filter on reality, described by some as having a “broken TV box in front of their eyes,” according to Lars Michels, a Swiss researcher involved in recent studies of the syndrome.

Beyond the ubiquitous static, visual snow syndrome is frequently accompanied by other symptoms. According to the National Institutes of Health, these can include sensitivity to light, migraines, and a ringing or buzzing in the ears, a condition known as tinnitus.

These co-occurring symptoms can also be quite disruptive. For instance, migraines can be painful enough to prevent people from carrying out daily activities, while tinnitus can make concentration and hearing difficult, as noted by the Mayo Clinic.

The condition is considered rare, with estimates from the Mayo Clinic suggesting it may affect up to 2% of the world’s population. However, due to its rarity and the ongoing nature of research, experts caution that not enough studies have been conducted to gain a truly accurate understanding of its prevalence worldwide.

A 2020 survey involving 1,100 people living with visual snow syndrome provided valuable insights into the demographics and onset of the condition. The study found that the average age of patients was 29, aligning with findings that symptoms often begin early in life.

Remarkably, nearly 40% of those surveyed in the 2020 study reported experiencing symptoms “for as long as they could remember,” highlighting a significant subset of individuals for whom this visual distortion has been a lifelong companion. The condition does not appear to worsen over time.

Diagnosing visual snow syndrome can be a process of elimination. It is typically diagnosed based on the constellation of symptoms a person reports, but only after other potential conditions that could cause similar visual disturbances or associated symptoms have been thoroughly ruled out by medical professionals.

Because research into visual snow syndrome is still in its early stages, experts are not yet certain about its exact cause. However, emerging studies are starting to offer clues about what might be happening within the brain.

A 2022 review of research suggested that visual-processing centers within the brain play a role in the disorder. Other studies have indicated a potential link between brain injury and an increased likelihood of developing visual snow syndrome.

Lars Michels offers an intriguing perspective on the potential neurological basis, suggesting that visual snow might be related to an overloading of the brain’s visual-processing capabilities. “There’s probably too much fuel in the tank for these people, and the brain cannot deal with it because it’s overloaded with information,” he explained.

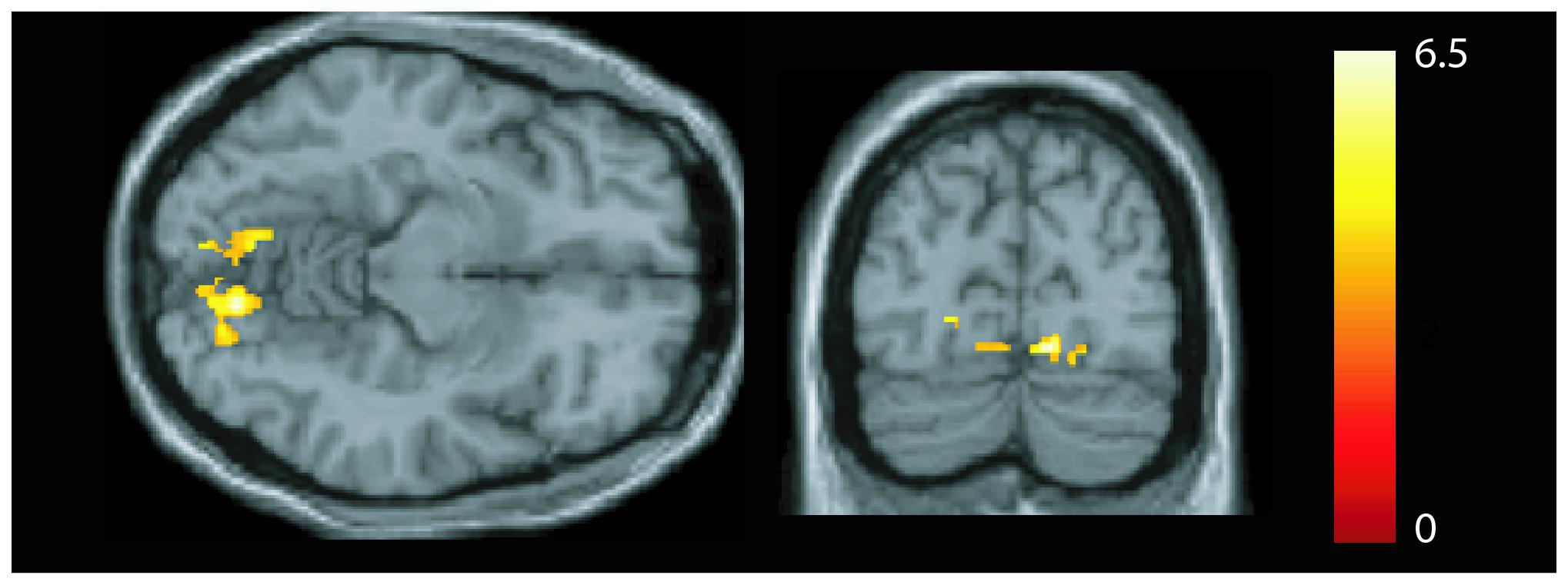

This constant overload may force the brain to work harder. Michels’ research, which involves analyzing brain images of patients, has observed that a specific part of their brains appears expanded. This abnormal growth is suspected to be linked to the symptoms of visual snow.

Michels describes this adaptation process as “maladaptive plasticity,” explaining that when a particular area of the brain is constantly bombarded by too much traffic and information, it adapts, leading to this observed structural change.

While there is currently no known cure for visual snow syndrome, some avenues for potential relief have been explored. One study indicated that a medication typically used to treat seizures and bipolar disorder showed positive results for some patients experiencing visual snow.

Additionally, anecdotal evidence suggests that wearing orange-tinted glasses might provide some degree of relief for certain individuals, though these are not considered cures but rather potential methods to alleviate symptoms.

Living with a chronic neurological condition like visual snow syndrome, for which there is no cure, can understandably take a significant toll on a person’s mental health. Studies have shown that people with the syndrome often experience challenges beyond the visual and auditory disturbances.

Conditions such as mild to moderate depression, anxiety, fatigue, and insomnia are commonly reported as side effects among those living with visual snow syndrome. These mental health impacts can significantly affect a person’s overall quality of life.

A 2021 study that surveyed 125 visual snow patients reinforced these findings. The study reported that “patients showed high rates of anxiety and depression, depersonalization, fatigue, and poor sleep, which significantly impacted their quality of life.” The research also noted that psychiatric symptoms, particularly depersonalization, were related to the increased severity of visual symptoms.

Depersonalization is a state where a person feels detached from their own body, mind, or surroundings. It can manifest as feeling like an outside observer of one’s own life or experiencing the world as unreal or dreamlike.

Lars Michels commented on this phenomenon, noting that depersonalization, or the feeling of being in a video game, is a common experience for those with visual snow syndrome. He explained that reliable vision helps the brain understand that it’s in a stable environment, and when bombarded by seemingly random visual and auditory disturbances, this can lead to a feeling that the environment is less grounded in reality.

The topic of visual snow syndrome has recently entered the public conversation in the context of the University of Idaho murder case. Reports have emerged suggesting that Bryan Kohberger, the 28-year-old suspect charged in the killings of four students, may have experienced this rare neurological condition and discussed his struggles with it online as a teenager.

A user on an online forum called Tapatalk, posting under the name Exarr.thosewithvisualsnow in 2011, wrote about having a condition called visual snow. The photo associated with the username was noted to resemble Kohberger.

News organizations, including Newsweek and The New York Times, have connected this Tapatalk account to Kohberger. Lauren Matthias, a true-crime podcast host, stated on NewsNation that she and her team had linked the account to an email account of Kohberger’s.

The New York Times reported that the Tapatalk username matched an email address belonging to Kohberger, that references to his birthday lined up with his known birth date, and that his listed location of Effort, Pennsylvania, matched Kohberger’s hometown. These details further strengthened the connection as attributed by reporting.

In a July 2011 post on the forum, the user Exarr.thosewithvisualsnow provided a vivid, albeit unsettling, description of their experience: “It is as if the ringing in my ears and the fuzz in my vision are simply all of the demons in my head mocking me.” This quotation captures the distressing nature of the symptoms.

Online records attributed to Kohberger suggest he turned to the internet during his teenage years to talk about the challenges posed by the condition. Posts on the Tapatalk forum, reportedly from 2009 to 2012, documented his journey with visual snow syndrome.

The user Exarr.thosewithvisualsnow wrote that the syndrome developed on September 21, 2009, when Kohberger was almost 15 years old. The user claimed that since the onset, they had changed, “mainly due to the anxiety, sense of derealization, and hopelessness.”

The forum posts reportedly detailed frequent struggles with memory access and feelings of depression linked to the condition. “Ever since then, I have been depressed,” read a post from 2010. (Quotations from his posts in this story are presented as he wrote them, unedited to conform with conventional capitalization and punctuation.)

The user continued in the 2010 post, expressing profound frustration and a sense of being trapped: “I can’t remember anything at all. And I always have this horrible pressure in my head… My mind is never not on visual snow, and I always wonder what a normal person would be doing while I sit there and suffer. This whole thing has made me crazy. I feel like my life is pointless because people can think about times with their parents/childhood memories and be happy, and I won’t be able to.”

The sense of depersonalization was also a recurring theme in the posts attributed to Kohberger. The Tapatalk user described a feeling of disconnection from life, likening their existence to playing a video game.

In one post from 2011, the user wrote, “I have had this horrible depersonalization going on in my life for almost 2 years. I often find myself engaging in simple human interactions, but it is as if I am playing a role-playing game.” This highlights the feeling of going through the motions without authentic engagement.

The user further elaborated on this feeling of detachment, stating that looking into the faces of family members felt like “looking at a video game, but less so.” This illustrates a profound sense of emotional distance even during intimate moments.

A particularly poignant post described the user’s experience during a family gathering: “As my family group hugs and celebrates, I am stuck in this void of nothing, feeling completely no emotion, just nothing. I feel dirty, like there is dirt inside my head, my mind. I am always dizzy and confused. I feel no self-worth.” This captures the isolation and distress potentially experienced.

Thomas Arntz, a former high school friend of Kohberger’s, recalled how consumed his friend seemed by the condition. He told the Idaho Statesman in a phone interview that Kohberger “would talk about it all the time.”

Arntz used strong words to describe the intensity of Kohberger’s focus on visual snow, stating that the word that came to mind was that he was “neurotic about it and talked about it relentlessly.” He added that the condition seemed to have a significant impact, saying, “I guess it truly bothered him to no end.”

The context indicates that learning about visual snow syndrome through Bryan Kohberger was the first time many people following the case had ever heard of this relatively little-known condition.

The online posts attributed to Kohberger also discussed attempts to find a cure for visual snow. In 2011, the user expressed a belief that they had discovered a way to cure the syndrome, theorizing it was caused by toxins resulting from consuming the wrong types of food.

The user wrote, “WHEN SOMETHING IS HAPPENING IN YOUR BRAIN THAT SHOULDN’T, CHEMICALS ARE BEING RELEASED THAT SHOULDN’T. THESE CHEMICALS ARE RELEASED BECAUSE WE HAVE TOXINS THAT OUR BODY DOESN’T WANT; IT IS GOING HAYWIRE.” This reflects a hypothesis about the condition’s origins.

The user pointed to a website called Know the Cause, which promotes the idea that many ailments are caused by fungi and yeast. Based on this, the user stated a plan to attempt to cure their visual snow through the diet recommended on the website, known as the Kaufmann Diet.

Read more about: The Warning Signs Christina Applegate Says She Missed Before Her MS Diagnosis: A Raw, Relatable Journey

Arntz remembered Kohberger trying to cure his visual snow through dietary restrictions. He told the Statesman that “Carbohydrates were a big no-no, and you had to stay away from breads, and absolutely no sugar.” Consequently, Arntz said, “mostly he would eat slices of ham and omelets.

The attempt to control visual snow through diet may have overlapped with other personal challenges. Many people interviewed recalled Kohberger’s considerable weight loss during high school.

Jack Baylis, another former friend, previously told the Statesman that Kohberger became “hyper-focused on what he ate,” to the point that he developed an eating disorder that required hospitalization. Arntz estimated that Kohberger had weighed more than 300 pounds and had lost as much as half his body mass.

Arntz suggested that Kohberger’s desire to lose weight might have intersected with his efforts to cure his visual snow. He recalled, “Bryan went on this diet in the hopes that his symptoms would go away. But it’s such a restrictive diet, and he’d cave in and try something else.” This illustrates the difficulty of maintaining such a strict regimen.

The final post from the Tapatalk account, dated February 19, 2012, was titled “Come to terms with the VS?” In this post, the user expressed a significant shift in perspective regarding the condition.

The user wrote, “I have finally accepted my visual snow. I don’t even feel the need to stay away from the forum; it doesn’t scare me anymore! Has anyone else come to terms with it? I feel like coming to terms could be a bad thing, though.” This post suggests a potential resignation or acceptance of living with visual snow.

It is important to note that while the context discusses the reported connection between Bryan Kohberger and visual snow syndrome, researchers emphasize the current understanding of the condition. Experts still do not know the definitive cause of visual snow syndrome, and there is no known cure; once developed, it is generally considered a lifelong condition.

The scientific community continues its work to understand the complexities of visual snow syndrome. Research into the visual-processing centers of the brain and the concept of maladaptive plasticity represents ongoing efforts to shed light on this challenging disorder.

The case of Bryan Kohberger, who is charged with four counts of murder and one count of burglary in connection with the killings of four University of Idaho students on November 13, has brought brief public attention to visual snow syndrome. A grand jury indicted him, and he is scheduled to be arraigned and officially enter his plea on Monday, May 22.

His attorney has not responded to requests for comment regarding the Tapatalk account or whether Kohberger has visual snow. Public defender Jason LaBar, who was assigned after Kohberger’s arrest, has stated that his client is innocent of the charges.

Neuroscientist James Fallon, discussing the online posts attributed to Kohberger, suggested that the notes about his mental state, including descriptions of living his life as if it were a video game, could point to a “dissociative disorder,” specifically a “depersonalization syndrome.”

Dr. Fallon explained that this condition, in which one feels separated from oneself, can result in an “extraordinary” struggle to empathize with others and with oneself. He described the brain’s GPS system that integrates sensory information and emotion, suggesting that this “apparatus seems to be damaged” when there is no connection with oneself or self-empathy.

Dr. Fallon noted that a lack of empathy towards others and oneself can sometimes be observed in psychopaths, though he was careful to state, “I’m not saying he’s a psychopath, but it’s such a curious combination of things.”

He also addressed the connection between visual snow and migraine, stating that it’s thought to be generated by “hyper-stimulated neurons at the base of the temporal lobe,” where visual processing occurs. He reiterated that visual snow is “debilitating, and almost nothing is known about it, but it is a syndrome that you never hear associated with murder.”

Crucially, Lars Michels stated that he is not aware of a connection between visual snow and aggression. He does not believe people should assume a link between Kohberger’s reported condition and his likelihood of carrying out an attack.

While the legal process for Bryan Kohberger is set to continue, the discussion surrounding visual snow syndrome highlights the ongoing scientific endeavor to understand complex neurological and psychological conditions. The exploration of symptoms, from pervasive visual static and associated physical ailments to the profound impact on mental states like depersonalization, underscores the intricate connection between brain function and lived experience.

Scientific investigations into the potential causes, whether related to brain processing overloads or other factors, continue to build upon the limited knowledge currently available. The journey to uncover effective treatments or even a cure for visual snow syndrome remains a critical area of research.

Ultimately, the reported struggles of one individual with a rare disorder underscore the broader importance of scientific inquiry into conditions that affect perception, mental health, and quality of life. Every new study, every documented experience, contributes to the slow but steady accumulation of knowledge that may one day bring clearer understanding and effective interventions to those who navigate the world through a haze of static.

Related posts:

What is visual-snow syndrome? Idaho murder suspect Bryan Kohberger may have discussed the rare disorder on an old chat forum.

U of Idaho homicides suspect had a rare neurological condition, visual snow. What is it?

The Idaho Murders, Part 1: How 4 College Kids Lived and Loved