Getting misdiagnosed felt like an itch inside my brain. It was one I simply could not scratch correctly. This persistent discomfort hits hard sometimes. It’s tough when the system meant to help doesn’t truly see you. You know something feels off inside you, but they say it’s located somewhere else entirely. Years passed, and I was always scratching the wrong place. Relief never arrived for me.

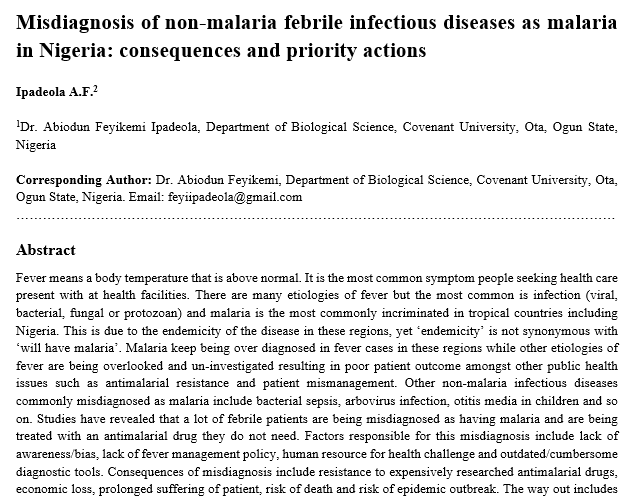

Lots of people go through this diagnostic maze, unfortunately. It shows a painful truth in mental healthcare for sure. Misdiagnosis happens quite often, really. This is especially true when symptoms don’t fit stereotypes easily, you see. My own story fits here too. I was first labeled with depression. Then it was bipolar disorder later. Finally, after a long time, the label became schizoaffective disorder.

Seeking mental health help started early for me. This was during my high school years. My first diagnosis ended up being depression mostly. To be fair, it wasn’t fully wrong, I guess. I cried often and felt low all the time. College felt like pure misery and torture for real. Suicidal thoughts came up pretty regularly for me then.

Some important symptoms got missed, however. These were overlooked even with clear signs of depression present. Nobody ever asked about sleepless nights. They didn’t ask about schoolwork that seemed strange. Or about periods where I often felt deep obsession. These pieces weren’t connected to the depression narrative. Treatment wasn’t provided because they weren’t recognized properly.

There was stuff I didn’t mention either. Things I assumed were normal for everyone. I didn’t tell anyone about floating lights, the auras I saw at night sometimes, or voices calling my name in the dark. I thought everyone experienced these things, you see. Accepting depression felt okay then. It helped explain some of my suffering a bit. Wellbutrin, an antidepressant, seemed to give me energy later. But my need for sleep stayed minimal. I started making grand, crazy plans after this. Plans so weird that sharing them would flag mania fast. Something fundamental was still missing. The diagnosis couldn’t explain all this discomfort.

Things changed dramatically at age 22, you see. This was during my first psychotic break. I felt intense discomfort for a week straight, like I was almost crawling right out of my own skin. This felt physically painful and mentally exhausting.

While in group therapy, it occurred. I started hallucinating intensely that day. The room turned green, looking strange. A giant bug appeared in the middle.

Its legs attached to everyone there were crazy. This clear psychotic event made my therapist act. She recommended I get psychiatric help quickly. This led to my being admitted to Bellevue Hospital. They made me admit to suicidality against my will, you see.

Five days later, I was discharged. I was given Risperdal, which is an antipsychotic. And a new misdiagnosis followed, you see. Next, it was bipolar disorder for me.

Despite clear psychosis, the focus stayed on suicide and the intense discomfort from the mixed state, you see. That’s painful manic energy mixed with a sad mood. It truly felt like nobody was putting the pieces together correctly.

They saw the symptoms but missed the correct picture then.

Even after a second hospitalization, things were strange. It was for another mixed state, like before. A doctor also suggested a sensory disorder then. But persistent psychosis seemed overlooked again. I was still on antipsychotic medicine, though. This left me utterly bewildered and confused. I didn’t know what was happening exactly. Feeling lost in my own head felt terrible. Years later, after I trained professionally, I wondered why I hadn’t seen the pattern before. But recognizing the diagnosis wasn’t my job, you know. It was always the psychiatrist’s responsibility. And across many providers over ten years, you see, they all failed to see the full picture clearly.

After that first hospital stay, I saw psychiatrists who struggled to treat me effectively. Over eight years with one specialist, I repeatedly reported my psychotic symptoms. Hallucinations of bugs were often mentioned. Delusions of body snatchers replacing my therapist were also there. Fear of leaving home due to perceived danger was present. Despite reports of psychosis with mood episodes always, every invoice bore the same label: Bipolar II, for eight years. My reality was filtered through the wrong lens then.

Now let’s talk about the overlap between ASD and BPD. This impacts women more often, you see. More attention is given to symptoms that look similar. Differentiating them is clinically challenging sometimes. ASD is a neurodevelopmental condition. It usually means challenges with social communication. It also involves feeling emotions strongly sometimes, which can look like frustration or anger outbursts, but also withdrawal and feeling down. Maybe it’s linked to sensory sensitivity differences or the intensity of feeling things inside. Another challenging aspect is repetitive behaviors, you know. This includes, sadly, hurting oneself. Self-harming behaviors like cutting or hair pulling are more common in people with ASD. The likelihood of self-harm in people with ASD is higher. It’s three times higher than in most people, unfortunately.

BPD is different; it’s a personality disorder. Feeling emotions is very hard sometimes, too. It causes frequent extreme mood swings. Anger outbursts are common with it. An intense fear of abandonment is a main sign. People with BPD can misunderstand others. They see disapproval in innocent looks or words easily. Impulsiveness is also a key trait. This impulsiveness often leads to self-harm behaviors, too. The statistics are very high, unfortunately. Around 60-70% of people with BPD attempt suicide. Ten percent actually die by suicide, sadly.

It’s simple to see the symptom overlap, you see, especially with emotion issues and self-harm. Clinicians must pay close attention when self-harm shows. They need to look deeper at why it happens. For people with ASD, self-harm might be a coping mechanism, a way to handle unease from sensory overload or changes in routine, maybe. For people with BPD, self-harm is different. It’s more likely driven by relationship pain and fears about being left alone often. Being alone feels different for each group. ASD individuals might usually enjoy time alone. It’s a chance to decompress and rest. BPD individuals feel intense abandonment fear when alone. Sharing difficulties with empathy is also a challenge. Struggling with understanding others’ perspectives happens. Plus, emotion issues and making friendships hard can make ASD look like BPD a lot, especially in women, it seems.

Read more about: MSNBC Anchor’s ‘Nightmare’ Health Scare: From Acid Reflux Misdiagnosis to Heart Inflammation

Women don’t often receive accurate ASD diagnoses. This is sadly true in both childhood and adulthood. They are frequently misdiagnosed with other conditions. BPD is one condition that is diagnosed before autism. Experts notice that several factors play a role in why autistic women fly under the radar, you know. One reason might be how girls are raised. They learn early to value fitting in well. Society tells them that social interaction is key. This might make them hide their autism signs. They try hard to blend in and avoid standing out. This often differs from males with ASD. Boys might show poorer social skills more prominently. They sometimes face clear social difficulties. Their autism presentation might be more obvious, based on traditional diagnostic ideas, you see.

Another surprising reason why diagnoses get missed exists. It relates to common restrictive interests. Autistic guys might like numbers or trains intensely. Autistic women might like books, psychology, or nature deeply. Or they might focus intensely on fictional characters, too. These interests are just as real, you know. But they might not be quickly seen as autism signs. Not compared to more stereotypically male interests, anyway. Females often possess stronger language skills, too. This helps them express their feelings more easily, you know. This ability seems good at first glance. But it can sometimes delay diagnosis, unfortunately. Communication challenges are a core aspect of autism diagnosis. Strong language skills make these challenges seem less clear, which makes it harder for doctors sometimes.

Social masking is a really big reason why autistic women get misdiagnosed a lot. Often, they are first diagnosed with anxiety, depression, OCD, or BPD before autism is even considered. Autistic women often copy social behaviors to blend in with others. Mimicking facial expressions happens. Scripting conversations takes place, too. Forcing eye contact always feels unnatural. This helps them navigate social spaces that are not natural to them. But this constant effort tires them out badly. It often leads to deep fatigue and burnout. Experts confirm that this masking is key. The exhaustion from it is also a sign. Overanalyzing social interactions happens. Stressing over missed social cues is real. These are signs of undiagnosed autism in adults, specifically in women.

Sensory sensitivities also play a part. How autism manifests is sometimes misunderstood. Overwhelm from loud noise is common. Bright lights affect them greatly. Certain clothing textures can feel uncomfortable sometimes. Strong smells can always be overwhelming.

These sensitivities manifest in various ways, you see. For instance, food aversions occur. Women are often labeled as picky eaters. Instead of recognizing that sensory processing differences exist and that they are part of an autistic profile, too.

Autistic women sometimes struggle with boundaries. They might experience burnout really fast. They are often seen as too sensitive. Struggling to say no is difficult for them.

They push themselves too much to meet expectations. Until they finally reach a breaking point. These struggles are sometimes misinterpreted. As personality traits or symptoms of other issues, you know, not connected to their underlying autistic neurology.

Getting a wrong diagnosis has significant outcomes. Its consequences are profound and far-reaching, you see. A major issue is that the treatment isn’t right. It never fits the person’s actual needs. Take BPD therapy like DBT, for instance. It helps regulate intense feelings and manage relationships. It targets relationship problems that are key to BPD. DBT helps many people—it’s true. But it’s usually not for someone with ASD. Applying BPD treatment to an autistic person means their real needs go unmet always. Needs like social communication support or sensory integration help, maybe. Navigating daily life from an autistic perspective is missed.

Wrong medication also happens, you know. This is sometimes common and serious. Psychotropic medications always have side effects. They can be annoying or truly dangerous. Giving an antidepressant to someone with bipolar disorder when they were misdiagnosed with depression can trigger dangerous manic episodes quickly. The long-term effects of unneeded medication are unknown. It’s vital that medication matches the true diagnosis. It must address the specific challenges correctly, based on an accurate understanding of all symptoms.

The psychological impact is also devastating. It makes people feel gaslit sometimes, you see. Especially if they felt the diagnosis was wrong before or that it didn’t fully explain things. This ignoring of their intuition creates issues. A difficult dynamic with their provider emerges, making it hard or impossible to speak up. It’s hard to be authentic in sessions about feelings or what they’re truly experiencing inside. This inability to self-report honestly is bad. Psychology and psychiatry rely heavily on this. There are no tests for mental illness, you know. If the provider isn’t getting real info, the client sometimes feels unable to share or tries hard to fit into the wrong box. How can the provider know how to help them well then?

When the diagnosis feels wrong, you might also feel wrong. You could always try twisting your experiences to fit symptoms into a wrong label you got, often because you trust the provider is an expert so much. They have credentials, right, you think? This is where misdiagnosis hurts most deeply. It convinces you to doubt your own reality and your expertise about your own life. The provider is an expert in clinical knowledge, yes. But you are always the ultimate expert on your own life. A wrong label erodes that fundamental self-trust deeply. Stigma associated with some diagnoses also adds harm, like the stigma sometimes attached to BPD. This impacts relationships and how you see yourself. Access to the right support also gets harder, even if the diagnosis given is completely wrong.

Read more about: Decades Later, a Father Jailed in Baby’s Death May Find Hope in Questioned Science

Leaving behind the initial confusion and distress of misdiagnosis, you find amazing stories. People who navigated systems faced many barriers but found ways toward validation and thriving. These stories, shared by others who had similar challenges, reveal a lot. They show the personal strength needed but also system flaws. It’s a path that often requires persistence and self-advocacy. Finding the right answer sometimes comes at a high cost.

Think about psychologist Dr. Amy Marschall and her experience. She lives with autism, anxiety, and also ADHD. Flags suggesting autism appeared since her early 20s, you see. A friend even pointed out some traits they shared. Her suspicions grew as she learned more about autism, too, especially about how diagnosis differs for women.

A big moment happened in 2020. Working from home allowed her to unconsciously drop the masking she had adopted. Seeking adult autism testing became hard, though. She is a mental health provider, creating dual relationship problems locally. Finally, a clinic that mostly assessed kids agreed to test adults anyway. Despite knowing the testers professionally, they deemed the relationship appropriate due to the lack of options for her. What followed was an eight-hour testing process. Pre-appointment tasks, input from her husband, and two interviews were also included.

The first results from this process were surprising. Dr. Marschall was told she didn’t meet autism criteria. Evaluators called her stims just fidgets and struggled to explain the difference. They noticed she made eye contact, which isn’t impossible for autistic individuals, you know. They inaccurately stated that it’s rare for autistic folks to marry and claimed that most autistics do not work full-time. While technically true about employment rates, it doesn’t mean none work.

Most alarmingly, her special interests were discounted because she got paid for them. She rightly calls this point absurd, you see. After all, many successful people’s careers monetize their passions. Dr. Marschall felt frustration; you could feel it. They knew she was married, employed, and applying for testing. They could have saved her money and time if they weren’t willing to diagnose someone with her background, regardless of the results.

The assessment used the ADOS-2, which some say is the gold standard. But it’s known for high false negatives in women. And her scores did indicate she was autistic. The clinic seemed to disregard the test results, maybe based on prior biases or her demographic. It was a frustrating failure within the system. Dr. Marschall wasn’t truly misdiagnosed; her other diagnoses were correct. Anxiety and ADHD were accurate diagnoses; she had them. But the crucial piece, the autism, was missed.

Sharing her story, an autistic friend said immediately, “That is bullshit; you are definitely autistic.” This spurred her to take action. She researched things extensively herself, interviewing 50 autistic folks about their diagnostic journeys and how their traits were not identified earlier. She joked about using her autistic hyper-focus for this deep dive into the topic. Her persistence led her to seek a second opinion from a provider someone she had interviewed had recommended to her. This second testing confirmed what she thought was true, indicating she met autism criteria but was high-masking. This high-masking made her traits easy to miss initially.

The cost of these tests was a lot of money. Neither evaluator took any insurance at all. She paid a total of $1600 for them both, although the second provider offered a discount that time. This money barrier is a key system problem too, highlighting why many folks simply cannot afford to get testing, let alone a second validating opinion later on.

Dr. Marschall’s story powerfully shows system barriers, you see: providers being biased based on outdated stereotypes, misinterpreting traits due to masking, disregarding test results and ignoring facts, and the very high cost of these tests. Her experience and others feed her advocacy work for supporting self-diagnosis and overhauling the diagnosis system. Her goal is to prevent folks from getting overlooked for unfair reasons. It underlines that a formal diagnosis is valuable, yes, but self-understanding and community validation are equally important always.

The journey through getting misdiagnosed affects people from more marginalized groups. An anonymous story by a therapist tells one experience: of a biracial African American and white man initially misdiagnosed with anxiety. His actual diagnosis was Bipolar II instead. This shows general disparities in mental health testing for BIPOC individuals, who often need more appointments to get the correct answer. This anonymous man’s misdiagnosis meant getting the wrong medication, with side effects possibly harmful to him. His therapist says the misdiagnosis impacted his social life too.

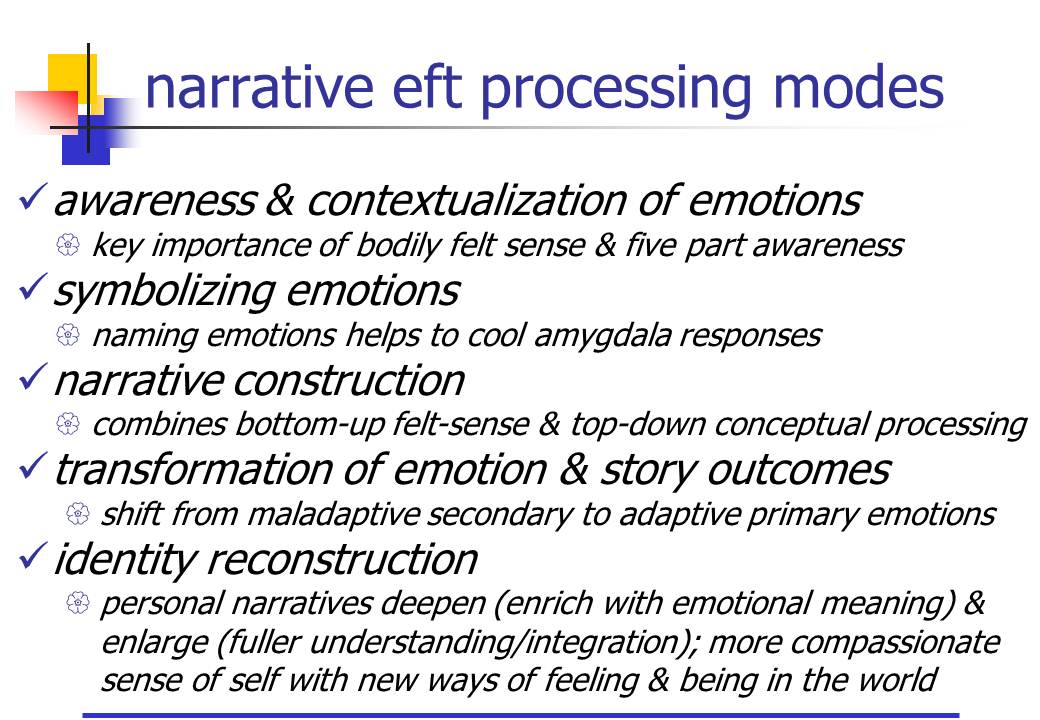

Part of their therapy involves narrative therapy, an empowerment approach that helps him find his voice. The aim is to live his true narrative. This therapy was important in helping him communicate well with his psychiatrist and advocate for himself effectively. It shows that the effects of misdiagnosis on the client-provider relationship can last a long time, even after the right diagnosis is finally made.

Sara Mendez’s story, that of a Latina woman, also shows this. She was initially misdiagnosed with bipolar I, borderline personality disorder, and schizotypal traits before her autism diagnosis. Years later, she finally received it. Her journey started with her boyfriend’s jokes about her interests, which sparked her thinking that she might have autism. Her main doctor dismissed her concerns too quickly, stating that she was nothing like his two-year-old son. This was a clear example of relying on narrow stereotypical views of autism at that time.

Undeterred, Mendez sought a full testing. This happened during the Covid-19 quarantine. A psychologist she found online gave her multiple diagnoses but dismissed autism because she made good eye contact via the camera and was just a very smart girl, she said, who didn’t know how to act like a normal human. Mendez initially trusted the professional’s credentials anyway. She endured months of useless and debilitating medication regimes. A breakthrough happened at her university center after an assault occurred there, and she went there for help.

A counselor who was autistic herself helped. She also researched autism in women. She immediately recognized Mendez’s symptoms. She suggested autism explicitly, linking misdiagnosis to her Latina identity. This counselor’s insight highlights critical roles for culturally competent providers and the severe impact of stereotypical autism views, which are often based on white boys—it’s a problem. Doctor Sandra León-Villa, an autistic Xicana psychologist, confirmed these differences, stating that Black and brown individuals generally face delays. Latine children are often diagnosed years later than non-Latine white youth. She notes that high-masking Latinas are likely to fall through the cracks easily.

She also links misdiagnosis to stereotypes. She explains that when autistic women, especially women of color, show traits like assertiveness or not having a filter at all, they are perceived as difficult or problematic instead by predominantly white providers. This leads to wrong diagnoses like BPD or bipolar disorder, not autism as it should be. Societal views of autism are heavily influenced by media research on white boys, which contributes significantly to these missed diagnoses.

Daniela Villada Londono came from Colombia to the U.K. Her autistic traits were flagged by school when she was around 10. However, language barriers initially stopped her parents from understanding. Later, they understood, but their own stigma around neurodevelopmental disorders stopped them. They felt stigma and hid it from her, fearing it would reflect badly on their parenting. Daniela learned the truth at 18 years old and pursued her diagnosis independently. She finally got it six years later, at age 24.

Jane, a New York sex worker who is trans, says she grew up in Puerto Rico. She finally got her autism diagnosis at age 26, after years of relatives saying her traits were just “manías.” Her being a trans woman of color makes things more complex. She states explicitly that anyone who doesn’t fit the basic white boy image often gets misdiagnosed. “So hey, that was me,” she commented. Her diagnosis, though late, brought clarity, explaining struggles like almost failing college and losing jobs too. “It wasn’t a fix, but it was vital, you see,” she said, “a piece of understanding herself better.”

These personal accounts show many barriers people face: biased providers lacking cultural knowledge, money hurdles, and outdated criteria too. Societal stereotypes are still a big one. Yet they are also stories of amazing perseverance. The path to getting validated means educating oneself and finding providers who know about autism in diverse folks. Sometimes, persistent self-advocacy is needed against significant resistance from others.

Getting the right diagnosis takes time and money sometimes. But it’s crucial for getting the right help later and understanding oneself better always. The National Autistic Society explains that diagnosis helps people understand themselves and find appropriate care pathways. It also provides a framework, language, and community. It can be very validating after years of confusion or feeling fundamentally wrong about oneself.

Thriving after being misdiagnosed isn’t about fixing a person, you see. It’s about matching the support with the real reality. As the author of the first part found out, she had schizoaffective disorder. Getting the right name and treatment, she says, allowed her to move from surviving to thriving instead. Similarly, an autism diagnosis, even if late, helps. It can unlock understanding of sensory needs, communication, and the need for specific accommodations that were previously missed completely.

System issues remain a problem, though. The high cost of testing and the lack of well-trained professionals affect many. Knowing the diverse presentations of autism is crucial. The persistence of stereotypes still makes the path hard for many. Doctor León-Villa argues that missed diagnoses harm everyone, not just the individual but the community too. They prevent early help and learning about autistic brains and contribute further to unfair stigma. The journey often involves taking back your own story and trusting your own feelings, even when professionals may disagree with you. The first section showed that misdiagnosis hurts this self-trust. The path to thriving rebuilds it, you see. Becoming the expert on your own life is key, advocating for the care you know is needed for you and seeking a second opinion as recommended. It’s not challenging authority but an act of self-preservation, a determination to find the right fit. Ultimately, these stories show the human spirit’s capacity for resilience when facing adversity.

They are also calls for change, you see, urging the mental healthcare system and society everywhere to move past stereotypes and biases now, to listen closer to the experiences people have lived, and to create pathways to accurate diagnosis quickly and appropriate support that is accessible, important, affordable, and culturally sensitive for everyone always, regardless of gender, race, or how they mask themselves. The goal is not just a diagnosis finally but a chance for everyone to understand themselves truly and live a life where they can thrive fully.

Related posts:

3 of Psychiatric Patients Are Misdiagnosed—Here Are Our Stories

Why Autistic Latinas Often Get a Late Diagnosis

Misdiagnosed: BPD or Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)?